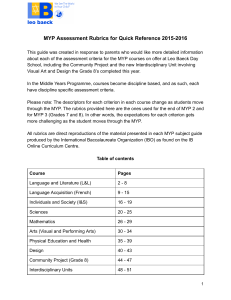

Uploaded by

sawicka_paulina

Developing a Personal Theory of Leadership

DEVELOPING A PERSONAL THEORY OF LEADERSHIP JAMES E. WILEY LDRS 812 FORT HAYS STATE UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT Leadership as an academic discipline is still in its development stage. As a field of study, leadership is relatively young yet already rich in information. Before a personal theory of leadership can be considered, a working definition of leadership should be established. It is within the framework of this definition that the elementary components of leadership may be found. Leadership is a transactional relationship between a leader and a follower or followers, in which their individual traits blend in varying situations, for the purpose of achieving mutually beneficial objectives. The following is an attempt to connect leadership as a recognized academic discipline to the development of a personal theory, what components a personal theory of leadership may consist of, and what the practical applications of a personal theory of leadership may be. To substantiate the components of a personal theory of leadership, past and present leadership studies will be taken into consideration. 1 COMPONENTS OF AN ACADEMIC DISCIPLINE RELATING TO LEADERSHIP As we undertake the work of developing a personal theory of leadership, identifying the constituents of an academic discipline can be helpful. Why should we make a connection between the academic characteristics of leadership studies and a personal theory of leadership? It is hoped that a personal theory of leadership will begin to emerge as we consider the elements of leadership as an academic discipline. After identifying the components of academic discipline, we can then ask whether leadership studies meets these criteria and if so, what we can derive about the essential elements of a personal theory of leadership. According to a study at Mountain State University by White and Hitt (Chen 2009), there is a widespread consensus that once academic disciplines are formed they “have become authoritative communities of expertise.” It is in the environment of this community of expertise that a personal theory of leadership will be discovered. According, to White, there are four modern systems used to classify disciplines; codification, level of paradigm development, level of consensus, and The Biglan model. The codification system arranges knowledge in a systematic order. The level of paradigm development suggests that as a discipline matures their paradigms become more defined. The level of consensus asks whether there is an agreed on set of goals, agreement of professional judgment by scholars, agreement on the body of knowledge, and a system to produce future scholars in the field. (Chen 2009). The Biglan Model is based on three dimensions of academia; “the degree to which a paradigm exists”, “the extent to which subject matter is practically applied”, and “the extent to which the field is involved with living or organic matter.” (Chen 2009) From these criteria we 2 can identify the central qualifiers of the academic discipline of leadership. The following is not a comprehensive list of opinions concerning the components of academic discipline and there continues to be debate over what the essential elements may be. However, the most common elements are: 1) A set of theories identified as belonging to the discipline 2) Distinctive methods of inquiry 3) An identifiable community of scholars of the discipline 4) A tradition of scholarly activity and inquiry (Chen 2009) Using these four components of an academic discipline, we can begin to consider the question. In the field of leadership studies, are the essential criteria met to validate it as an academic discipline which will help in the establishment of a personal theory of leadership? If the outcome of this evaluation is in the affirmative and leadership continues to grow as an academic discipline, then the possibility of a personal theory is greatly increased. The first criterion is whether there is a set of theories identified as belonging to the discipline. There are numerous theories and sub categories of theories that have been develop over the past one hundred to one hundred and fifty years. A few examples would be Fiedler’s Contingency Theory, Hersey and Blanchard’s Situational Theory, House’s Path-Goal Theory, and Vroom, Yetton, and Jago’s Normative Decision Making Theory. (Howell et al, 2006) In addition to these behavioral theories is Stogdill’s Trait Theory developed in the late 1940’s and revisited in the 1970’s. (Crawford et al, 2000) As Fred Fiedler stated, “There are almost as many 3 definitions of leadership as there are leadership theories—and there are almost as many theories of leadership as there are psychologists working in the field.” (Fiedler 1971) To say that leadership meets the first element of an academic would be an understatement considering the extensive research, study, and theory development that has taken place over the past century. The second criterion asks whether there are distinctive methods of inquiry. All of the theories mentioned have distinctive methods of inquiry, some more qualitative as in the study of traits, and others quantitative as in the study of emotional intelligence. (Northouse 2010) The third element to consider in academic disciplines is the scholars themselves who are researching the field. There is an extensive list of individuals from various disciplines who have contributed to the study of leadership. Among these are individuals who have been pioneers of thought in leadership like Stogdill, Feidler, Vroom, and House. (Chemers 1997) With more than sixty universities offering doctoral programs relating to leadership, the fourth element of an academic discipline, a history of scholarly activity, has without doubt, been established. As mentioned earlier, there are a multitude of theories from diverse perspectives that comprise the field. It is well within reason to agree that leadership studies sufficiently satisfy all the criteria of an academic discipline. This being true, we can now take the elements of the academic discipline of leadership criteria and extract the pieces that will provide a framework for a personal theory of leadership. Such an attempt was made by James MacGregor Burns. Over a five year period beginning in 2001, Burns pulled together a group of scholars for the express purpose of developing what he called a personal theory of leadership. (Goethals et al 2006) Even after 4 eight separate meetings, each one lasting several days, the assembly fell short of their declared purpose. This is not to diminish the considerable progress that was made in identifying some essential elements of a personal theory of leadership. (2006) We can draw from the abundant research of recognized scholars and identify 1) consistencies in study outcomes and, 2) congruent philosophies which work in concert though they are often categorized as individual theories. COMPONENTS OF A PERSONAL THEORY OF LEADERSHIP For the purpose of laying a foundation for a personal theory of leadership we need to identify the major theory concepts that have been discovered during the span of leadership study. I would contend that all studies and sub-theories of leadership can be categorized in one of the following three major “houses” of leadership theory: 1) Behavioral / Trait, 2) Contingency / Situational, 3) Transformational / Transactional. There is some overlap in these components with some discoveries serving as a portal to the next era. A good example of this is Stogdill’s trait studies which led him to believe that traits alone do not explain the effectiveness of a leader, rather effectiveness is a combination of both leader’s characteristics and variables of the situation, followers, and goals which led to the era of contingency / situational theory. (Chemers 1997) These overlaps can be seen as covered breezeways where ideas and applications are shared. While there is bountiful research from many scholars in each of these approaches to leadership studies, for the sake of practicality, only the central elements of these three building blocks will be discussed. As other studies are taken into consideration, it becomes clear that they are in fact, sub-facets of the major theories. 5 Behavioral / Trait Component of Leadership Theory Trait theory was considered antediluvian as contingency theories emerged, however, there has been a reemergence of the study of traits as evidenced by articles like Personality And Leadership: A Qualitative And Quantitative Review, in the Journal of Applied Psychology by Judge, Bono, Ilies, and Gerhardt. (Day et al, 2008) We cannot overlook the consideration of an individual’s composition of character as the first building block of leadership in a personal theory of leadership. Early studies of leadership were almost exclusively focused on traits held by the individual leader. Though trait theory resulted in frustration due to an inability to reach consistent outcomes, and the inconsistency of the studies themselves, later work in the 1980’s by Stephen Zaccaro indicated, “Stable aspects of a leader can indeed have predictive validity.” (Chemers, 1997) By this we understand that it is possible to predict with some reasonable expectancy of outcome, the long term effectiveness of an individual in a leadership role if they possess certain traits. Another way to state this is if an individual is deficient in certain traits, their leadership effectiveness is predictably minimized if not nullified altogether. Whether learned by environmental influence or innate, every effective leader exhibits personal characteristics which contribute to the process. While there could be thousands of words to describe leader traits, we can select the major traits that are consistent in past studies. Based on past and present studies of trait theory, there are five reoccurring traits that have an impact on leadership: Cognitive Intelligence, Resilience, Charisma, Integrity, and Social Intelligence. Although the terminology may be interchangeable, the essence of at least 6 one, if not several, of these five traits was noted as leadership traits in six major trait studies, including Stogdill (1948), Mann (1959), Stogdill (1974), Lord, Devader, and Alliger (1986), Kirkpatrick and Locke (1981), and Zaccaro, Kemp, and Bader (2004). (Northouse, 2010) Cognitive intelligence includes “perceptual processing, information processing, personal reasoning skills, creative and divergent thinking capacities, and memory skills.” (Northouse 2010) If the leader’s cognitive intelligence is significantly lower than followers, the effectiveness of their leadership is diminished greatly. Locke argued that cognitive ability is valuable to leaders given their responsibility to gather and process large amounts of information. (Locke 1991) Resilience can be defined as the ability to recover and adjust to difficult situations, especially when they embody hardship and suffering. Resilience not only gets a leader through tough situations, it can actually increase productivity helping the leader learn how to deal with adversity in the future. (Sutcliffe 2003) Charisma, as defined by Weber (1947), is a “special personality characteristic that gives a person superhuman or exceptional powers and is reserved for a few, is of divine origin, and results in the person being treated as a leader.” A wonderful example of a charismatic leader would be Martin Luther King Jr., whose inspirational speeches motivated the masses toward social change during the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960’s. Charismatic leadership is effective because it links followers and their belief about themselves to the identity of the organization or movement. (Northouse 2010) 7 Integrity is a trait that is usually not noticed except when absent. The leader follower relationship is one of trust. According to Chrislip and Larson, in order for leaders and followers to collaborate successfully over a long period of time, it is essential that an atmosphere of openness and trust be established and sustained. (Chrislip et al 1994) The power of the leadership position is deeply affected by the level of trust between leader and follower. Leaders who have the trust of their followers have more power and need less power to lead. Contrarily, leaders who do not have the trust of their followers have less power and need more power to lead. The combination of faith and security in the integrity of a leader is indeed powerful. (Goethals 2006) Social intelligence “capacities refer to a leader’s understanding of the feelings, thoughts, and behaviors of others in a social domain and his or her selection of the responses that best fit the contingencies and dynamics of that domain.” (Zaccaro et al 2004) Social intelligence knows how to get along with people in varying situations and create the best opportunity for the individual and the organization to benefit from the relationship. Dale Carnegie’s book, How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936), is an excellent tutorial on how to develop social intelligence without being manipulative or controlling. As Carnegie eloquently points out, “Dealing with people is probably the biggest problem you will face,” and about 85% of one’s financial success is, “Due to skill in human engineering – to personality and the ability to lead people.” (Carnegie 1936) Situational / Contingency Component of Leadership Theory 8 In 1948, Stogdill acknowledged that leadership theory would not be complete unless it included a combination of the leader’s personality and the situation the leader found themselves in. Contingency / Situational theories blend the behavioral tendencies of the leader with the leader situations or scenarios they encounter or create. (Chemers 1997) Fred Fiedler’s Contingency theory is the most widely researched model on leadership. (Bass, 1990) Contingency theory based on the Least Preferred Co-worker scale, addresses what type of leaders respond well in particular situations. Fiedler describes the leadership phenomenon in three dimensions, the leader-member relations, task structure, and leader’s positional power. Fiedler’s model, showed that low LPC (task-oriented) leaders performed better when leadermember relations, task structure, and leader’s positional power were highly favorable or unfavorable to the leader. High LPC leaders, (relationship-oriented), performed better when the three dimensions of leadership were not high or low, but moderate. (Bass, 1990) Fiedler found that low LPC (task-oriented) leaders were more likely to perform in a dominant manner regardless of the leadership dimensions. Using this scale, R.W. Rice further refined the LPC categorizing 1,445 relationships that exist within the LPC model. Rice found that leader LPC scores, whether high or low, stayed fairly consistent. (Rice 1983) Being able to predict the type of situation a leader was best suited for allows for the potential of pre-planning where to place a leader given their strengths. Additionally, if the possibility of adjusting the work situation to either a more task orientation or relational orientation exists, then a leader can modify the situation to fit their personal leadership strengths. The more comfortable a leader is in a given situation, it is more likely their leadership will be effective. According to Chemers, when a “psychological state characterized by excitement, confidence, and personal responsibility” 9 exists, there is a greater possibility that a “positive environment for productivity and effective leadership” will exist as well. (Chemers 1997) Hersey and Blanchard build on the task-oriented or directive behavior, and the relationship-oriented or supportive behavior of leaders in their situational leadership theory. They developed a four quadrant model. Quadrant 1, called Telling consists of highly-directive and low supportive style of leadership. Quadrant 2 called Selling consists of a highly-directive and highly supportive style of leadership. Quadrant 3 called Participating consists of a lowdirective and highly-supportive style leadership. Quadrant 4 called Delegating consists of lowdirective and low-supportive leadership style. According to Hersey and Blanchard, quadrant 1 represents a low follower readiness, meaning the follower has a low ability and low willingness to accomplish a task. Quadrant 2 represents those followers who have a high willingness but a low ability. Quadrant 3 represents followers who have a high ability but a low willingness. Quadrant 4 represents followers who have a high ability and a high willingness to accomplish a task. (Hersey 2008) The simplicity of this theory makes it inviting for easy application, however, subsequent research has failed to show consistent results, especially in the Telling and Delegating quadrants. (Howell 2008) Another significant theory that is housed in the Contingency / Situational family, is the Normative Decision Making Theory (NDMT) first developed by Vroom and Yetton and later revised by Vroom and Jago. Some studies leading up to the NDMT were House’s Path Goal Theory and Yukl’s Multiple Linkage Theory. However, though these studies served to make a connection between leadership styles and the situational factors, they were not specific enough 10 to be tested in a reliable manner and therefore made predictions difficult and inconclusive. (Howell 2008)NDMT “contends that the effectiveness of a decision depends on applying a decision-making style that matches the situation.” (Howell 2008) That is to say, that the five decision making styles: Decide, Consult Individually, Consult Group, Facilitate, and Delegate as identified in the NDMT, if appropriately applied to situations will determine the effectiveness of the leader’s decisions in six ways: Decision Acceptance, Decision Quality, Decision Timeliness, Costs of Decision Making, and Follower’s Development. (Howell 2008) There is evidence according to Vroom and Jago that the NDMT is predictably accurate, however, there has been limited research to verify it. The drawback of the NDMT model is that it is somewhat complex, and not all leaders are likely to have the capacity to apply all five of the decision making styles. One thing we can be reasonably sure of is Contingency / Situational theory needs to be included as one of the foundational components of a personal theory of leadership. Transformational / Transactional Component of Leadership Theory To say that leadership/behavioral traits and situational/contingencies equate leadership falls short of the leadership definition. Leadership is a transactional process between the leader and followers. Perhaps the most substantiated study in leadership can be identified as transactional / transformational theory. Transactional leadership could be described as an informal exchange or transaction between leaders and followers in which the follower provides a competent effort, and the leader provides directive influence. (Howell, 2006) Within the context of transactional leadership are multiple factors that contribute to the relationship of leader and follower. Bass’s (1995) Multi-factor Leadership Questionnaire is a tool that has been 11 used to measure transactional leadership relationships. Bass’s conceptualization of transactional and transformational leadership included seven leadership factors, which he labeled Charisma, Inspirational, Intellectual Stimulation, Individualized Consideration, Contingent Reward, Management-By-Exception and Laissez-Faire Leadership. (Avolio et al, 2010) The distinction between transactional and transformational leadership is based on what is being exchanged between leader and follower. In transactional leadership, the leader is offering reward for productivity. Transactional leadership takes place when "one person takes the initiative in making contact with others for the purpose of an exchange of valued things." (Burns 1978) Transformational leadership refers to the leader’s inspiration of followers to “achieve extraordinary outcomes and, in the process, develop their own leadership capacity.” As Burns points out, there is a moral element in transformational leadership, whereas transactional leadership is equivalent to a politician providing benefits in exchange for votes. (Bass et al, 2006) Burns (1978) asserts “The result of transforming leadership is a relationship of mutual stimulation and elevation that converts followers into leaders and may convert leaders into moral agents.” Transactional / transformational theory must be included in a personal theory of leadership because it is an overarching covering for all leader/follower interactions. Housed in the theory of transactional / transformational leadership we can categorize many studies in. Some notable categories of leadership studies that qualify for this component of leadership theory are Power/Influence Leadership, Servant Leadership, Team Leadership, Collaborative Leadership, Directive Leadership, Supportive Leadership, And Transcendent Leadership. A closer look at each of these leadership relationships is highly dependent on exchanges between leader and follower. The interactive aspect of leader follower relationships 12 substantiates the fact that they can be consolidated under the umbrella of transactional/transformational leadership. In the Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Stone et al (2004) posit there is a difference in the focus of the leader in transformational leadership and servant leadership. However, the servant leader, while being concerned with the follower’s success, must recognize that there is a direct link to the organization’s success and that is critical to their survival. Team leadership and collaborative leadership are closely related as demonstrated in LeFasto’s Team Excellence and Collaborative Team Leader Surveys. The survey asks seven questions that deal with team effectiveness, structure, and health of the team. The next six questions deal with leadership effectiveness. (Northouse, 2010) To further emphasize the similarities of team and collaborative leadership, effective team leaders make certain there is a collaborative atmosphere which makes communication safe, demands and rewards collaborative behavior, guides team’s problem solving, and manages their own need of control without being overbearing. (LaFasto et al 2002) The difference in team leadership and collaborative leadership is the size of the group. Teams are smaller and more intimate, while collaborative leadership can occur in large segments of society for a common cause. Collaborative leadership is one which can be applied to entire communities and regions. (Chrislip et al 1994) The relationship between leader and follower in teams and in collaborative situations is critical to successful outcomes and is a vivid picture of transactional / transformational leadership. 13 Directive leadership occurs when the leader defines both the objectives and the methods for a group to accomplish specific performance goals. (Hellriegel et al 1998) The transaction between leader and follower, though less negotiable, is none the less transactional. Supportive leadership is recognized as a leader concerns themselves with the development of the follower by demonstrating a caring and understanding disposition. (Howell et al 2006) Supportive leadership meets the second highest human need as defined by Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, the need for esteem. (Maslow 1943) Perhaps the most progressive element of transformational/transactional leadership is transcendent leadership. As author John Jacob Gardiner states, “The transcendent leader invites others into a consciousness of the whole.” (Gardiner 2006) A transcendent leader not only helps others accomplish self-actualization, but communicates values in such a way that followers take on those same values, visions, and purpose and become part of the whole. There are six necessary steps for transcending leadership to be complete; a climate of trust, information sharing, meaningful participation, collective decision making, protecting divergent views, and redefining roles by recognizing all members are leaders. Transcendent leadership, though new to the paradigm of leadership studies, still is categorically a relational exchange falling under the greater umbrella of transactional/transformational leadership. Again, in each of these relationships, an exchange has taken place between leader and follower for the sake of achieving a mutually beneficial goal. The one other major component of transactional / transformational leadership is the power/influence. Power is the potential ability of one person to influence other people to bring 14 about desired outcomes using either hard or forced power, or soft power based on influence. Influence refers to the effect a person’s actions have on the attitudes, values, beliefs, or actions of others. Whereas power is the capacity to cause a change in a person, influence may be thought of as the degree of actual change that the person embraces. However, power, whether hard or soft, is still the ability to affect change through a transactional or transformational exchange between leader and follower. According to the 1959 study by French & Raven, there are five bases of power: referent power, expert power, legitimate power, reward power, and coercive power. (Northouse 2010) Each of these bases can be readily identified with either power or influence. Coercive power is most likely to be related to hard power – the ability to force behavior. Legitimate power could also be identified with hard power because their position gives them the authority to exact judgments without the necessity of cooperative agreement, however, it is can also be administered as soft power depending on the disposition of the leader. Expert power, referent power and reward power are all based on a relationship of influence rather than force. They are examples of power through influence or soft power. David Ingram states, “Transactional leaders use disciplinary power and an array of incentives to motivate employees to perform at their best.” (Ingram) This is in direct correlation with a combination of legitimate power and reward power which is behaving in a transactional manner to lead an organization. The parallels of transactional/transformational leadership and power/influence leadership are so closely related that housing them under the same pavilion of a personal theory of leadership is both functional and logical. 15 According to Atwater and Yammarino, their study of the relatedness between transactional/transformational leadership and power revealed that referent and expert power were related to transformational leadership. Transformational leadership also indicates a correlation with reward and legitimate power, although as one may expect, not with coercive power. The study seems to imply that leaders who behave in a transformational manner are likely to possess positive bases of power. There is further indication that transformational leaders are effectively influence group members as the members recognize their referent power base. According to Atwater there is significant support for the interrelatedness of transformational/transactional leadership and power. (Atwater 1996) Summary of Major Components of Leadership Theory What we have proposed is that there are three houses or families of leadership theory. Within each house are numerous studies and sub-theories that explore the complexities of human relationships as relating to leadership. These three houses are interconnected yet each one houses specific families of thought concerning leadership theory. Together they form a community of leadership. Community is a portmanteau of common and unity. The term community is appropriate for a personal theory of leadership. The commonality is present in that while there are unique components of theory, they have in common the central theme of effective leadership. Unity of 16 purpose and a personal agreement by scholars in the field is a key to reaching a personal theory which will be widely accepted, recognized, and adopted. It should not be misconstrued that this article has included every important study or theory of leadership. What can be understood is that every study of leadership theory can be found under the covering of one of these three roofs. For example, though not explicitly mentioned, power, mentoring / coaching, equity, gender, ethics, and many other topics are woven in the fabric of one or more of the above houses. As experts in the academic discipline of leadership come to a personal agreement about the major components of leadership theory, the possibility of a personal theory of leadership will be within reach. For the moment, it appears that the criterion for the academic discipline of leadership has proven to be effective in development of a personal theory; however, the arduous task of finding agreement from diverse scholars is still before us. The three houses of leadership theory that we have identified are: Behavioral / Trait, Contingency / Situational, and Transactional / Transformative. Housed in each family are multiple studies and sub theories that often overlap and complement each other. Below is a graphic that helps to visualize the community of leadership theories. 17 Community of Leadership Theory Behavioral / Trait Contingency / Situational R.W. Rice – Refined LPC Hersey & Blanchard – 4 Quadrant model Vroom & Yetton - NDMT Cognitive Intelligence Resilience Charisma Integrity Social Intelligence Transactional / Transformational Servant Leadership Team Leadership Collaborative Leadership Directive Leadership Supportive Leadership Transcendent Leadership Power/Influence Leader 18 Applying a General Theory of Leadership What might be the purpose of developing a general theory of leadership? Burns primary goal as he called together a collection of scholars from multiple disciplines for the purpose of developing this general theory of leadership, was to hopefully prevent the fragmentation of leadership studies and in the process create a sense of intellectual unity and coherence to the field of leadership. In this way, Burns believed that there would be less inclination of some skeptics to trivialize the study of leadership, viewing it as “ill-defined.” (Goethals 2006) Burns further addresses his quest for a personal theory of leadership stating that he hoped to, “provide people studying or practicing leadership with a personal guide or orientation- a set of principles that are universal which can be then adapted to different situations.” (Goethals 2006) Lynham and Chermack believe that there is growing demand on leadership to address post modern issues in business. These would include a shortage of skilled labor, globalization of business, and balancing people and performance needs. A general theory of leadership could help to “make sense” of the current theories, and increase their performance. (Lynham 2006) Certainly the successful application and practice of leadership principles is the goal of theory development. Study for the sake of study in a field of leadership is like running in circles, at some point we need to get off the merry-go-round of rumination and move on to application. Not to say this is not already the case, however, by establishing a widely accepted personal theory of leadership, the processes of application will become more prolific. Leadership is about effecting real change. It is the nature of mankind to become more effective, productive, and progressive. Our quest is for more than theories that meet certain standards of scientific credibility. We are on a quest to better ourselves, our organizations, and our world. 19 References: A. Gregory Stone, Robert F. Russell, Kathleen Patterson, (2004) "Transformational versus servant leadership: a difference in leader focus", Leadership & Organization Development Journal, Vol.25 Iss: 4, pp.349 - 361 Atwater, L. and Yammarino, J., “Bases of Power in Relation to Leader Behavior: A Field Investigation,” Journal of Business and Psychology, Fall 1996, pp. 3-22. Avolio, B., Bass, B., Jung, D., Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology (1999), 72, pp. 441–462 Printed in Great Britain Ó 1999 The British Psychological Society Bass, B. M. (1990). Bass & Stodgill’s handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (3rd ed.). New York: The Free Press. Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership. (2nd ed. ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum. Burns, J.M. (1978). Leadership. New York: Harper & Row Carnegie, D. (1936). How to win friends and influence people. New York: Gallery Books. Crawford, C. B., Brungardt, C., & Maughan, M. (2000).Understanding leadership behavior. (pp. 31-35). Longmount: Rocky Mountain Press. Chrislip, D., & Larson, C. (1994). Collaborative leadership. (1st ed. ed.). San Francisco: JoosseyBass Publishers. Day, D., & Antonakis, J. (n.d.). Leadership: Past, present, and future. (2008). Sage Publications, 7, 8. Retrieved from http://www.sagepub.com/upm-data/41161_1.pdf 20 Fiedler, F. E. (1971). Leadership. Morristown, NJ: Personal Learning Gardiner, J. J., “Transactional, Transformational, and Transcendent Leadership: Metaphors Mapping The Evolution Of The Theory And Practice Of Governance,” Kravis Leadership Institute Leadership Review, Vol. 6, 2006. pp. 62-76. Goethals, G. R., & Sorenson, G. L. J. (2006). The quest for a personal theory of leadership. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. Hellriegel, D., Slocum, J.W. Jr., Woodman, R.W. (1998). Organizational Behavior, 8th ed. Cincinnati, Ohio: Southwestern. Hersey, P., Blanchard, K., & Johnson, D. (2008).Management of organizational behavior. (10th ed.). Boston: Pearson. Howell, J. Costley, D. (2006). Understanding behaviors for effective leadership. (2nd ed., pp. 4159). New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Ingram, David. "Transformational Leadership Vs. Transactional Leadership Definition." Chron. n.d. n. page. Print. <http://smallbusiness.chron.com/transformational-leadership-vstransactional-leadership-definition-13834.html>. LaFasto, F. M. J., & Larson, C. E. (2002). When teams work best, 6,000 team members and leaders tell what it takes to succeed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. Locke, E. A. (1991). The essence of leadership. New York: Lexington Books. Lynham, S.A. , Chermack , T. J - Responsible Leadership for Performance: ATheoretical Model and Hypotheses, Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies, 2006, Vol. 12, No. 4 21 Maslow A.H., A Theory of Human Motivation, Psychological Review 50(4) (1943):370-96. Northouse, P. (2010). Leadership, theory and practice. (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. Rice, R. W., & Kastenbaum, D. R. (1983). The contingency model of leadership: Some current issues. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 4(4), 373-392. Sutcliffe, K.M., & Vogus, T. 2003. Organizing for resilience. In K.S. Cameron, J.E. Dutton, & R.E. Quinn (Eds.), Positive Organizational Scholarship, 94-110. San Francisco: BerrettKoehler. Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organizations (T. Parsons, Trans.). New York: Free Press Zaccaro, S. J., Kemp, C., & Bader, P. (2004). Leader traits and attributes. In J Antonakis, A.T. Cianciolo, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The nature of leadership (p. 115). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. 22